|

|

Tuesday, February 13, 2024

|

|

|

|

By Stephen Halbrook

On February 7, the Supreme Court of Hawai'i decided State v. Wilson, upholding state criminal laws confining handguns and ammunition to the "possessor's place of business, residence, or sojourn." A separate provision provides for permits to carry (which historically no one got), but the defendant had not applied for a permit and thus had no standing to challenge that provision. Article I, § 17 of the Hawai'i Constitution has the same language as the federal Second Amendment, just deleting the first and last comma. Wilson held that § 17 "supports a collective, militia meaning," and thus "in Hawai'i there is no state constitutional right to carry a firearm in public." Citing Justice Stevens' dissent in Heller and Justice Breyer's dissent in Bruen, Wilson claims that the U.S. Supreme Court "distorts and cherry-picks historical evidence. It shrinks, alters, and discards historical facts that don't fit." The Court's failings are not limited to the issue at hand – "the Dobbs majority engaged in historical fiction" as well. Wilson avers: "The United States Supreme Court disables the states' responsibility to protect public safety, reduce gun violence, and safeguard peaceful public movement." Wilson fails to analyze the actual precedents when it asserts: "Until Heller, the Supreme Court had never ruled that the Second Amendment afforded an individual right to keep and bear arms." Well, the Court assumed that the right is individual in Scott v. Sandford (1857), U.S. v. Cruikshank (1876), Presser v. Illinois (1886), Robertson v. Baldwin (1897), U.S. v. Miller (1939), Johnson v. Eisentrager (1950), and U.S. v. Verdugo-Urquidez (1990). According to Wilson, both § 17 and the Second Amendment "use military-tinged language – 'well regulated militia' and 'bear arms' – to limit the use of deadly weapons to a military purpose." However, "there are no words that mention a personal right to possess lethal weapons in public places for possible self-defense." But this ignores that the guarantee has two separate clauses – one declaring the necessity of the militia, the other declaring the right of the people to bear arms. Wilson implies that the militia are the only "people," as if the guarantee refers to "the right of the militia to bear arms." The court doesn't bother to compare the usage of "the people" with other parts of the state Bill of Rights, which prohibits abridgment of "the right of the people peaceably to assemble," provides that "the right of the people to privacy … shall not be infringed," and guarantees "the right of the people to be secure … against unreasonable searches, seizures and invasions of privacy…." By contrast, in the very next provision after the arms guarantee, the drafters knew how to distinguish "the people" from "member[s] of the militia" by providing that "no soldier or member of the militia" may be quartered in any house except in certain circumstances. Quoting Justice Stevens' dissent in Heller, the court stated that "when used unadorned by any additional words, its meaning [i.e., bear arms] is 'to serve as a soldier, do military service, fight.'" But there are additional words – the "right" of "the people" to bear arms. The court acknowledged that most state constitutions protect individuals because they refer to "persons" and "citizens," but ignores that several also refer to "the people." Many follow variants of Pennsylvania's 1776 Constitution by stating that "the people have a right to bear arms for the defence of themselves and the state." But, says Wilson, § 17 doesn't refer to "defence of themselves." Right, but it also doesn't refer to "defence of the state." It generally recognizes the right to bear arms, impliedly for all lawful purposes, just as the U.S. Supreme Court did in the Heller decision. The fun begins when the court sought to explain the public understanding when the guarantee was adopted in 1950, but leaves out critical parts of that history. In written testimony to the Hawai'i legislature in 1992 in opposition to a proposed ban on semiautomatic firearms, I had occasion to research the 1950 proceedings. The legislature ended up banning only what it called "assault pistols" defined by certain generic features. Below are some of the critical items that Wilson left out. Wilson does not mention the manual prepared by the Legislative Reference Bureau and distributed to all members of the 1950 constitutional convention, which stated: "The rights of persons may be considered under two categories – the rights of persons in normal course of living (civil rights), and rights of persons accused of crime. Under the first category may be included the freedom of speech and press, of assembly, of conscience (religion), and the right to bear arms." Manual on State Constitutional Provisions Prepared for the Constitutional Convention, Territory of Hawaii 345 (1950). Wilson quotes a committee report stating that the guarantee "incorporates the 2nd Amendment" but "should not be construed as to prevent the state legislature from passing legislation imposing reasonable restrictions upon the right of the people to keep and bear arms." Stand. Comm. Rep. No. 20. But Wilson neglects that Delegate Jack H. Mizuha, Chairman of the Committee on Bill of Rights, read those very words when bringing the provision before the convention and explained that the term "the people" "applies to all persons here in the territory." Delegate Phillips asked, "To each individual or to them as a group? … Well, you say … 'the militia,' and then … after the comma, 'the right of the people to keep and bear arms.' Do you mean there the right of the individual or the right of the – …." Mizuha replied, "All individuals. … Individual rights, the Constitution is for individuals." 2 Proceedings of the Constitutional Convention of Hawaii, 1950, at 11-12 (1961). Mizuha also noted that the Committee heard from representatives of rifle clubs and gun clubs, who obviously supported the guarantee to support their rights, as well as police and prosecutors, who wished to keep current restrictions. If the guarantee was thought to protect the "right" of the National Guard to bear arms, why weren't Guard spokespersons testifying in its favor? In further debates, reference was made to the restrictions on machine guns in the National Firearms Act. The delegates were assured that the arms guarantee would not prevent banning such weapons. But no one suggested that commonly-possessed rifles, shotguns, and handguns could be banned. Delegate Bryan supported the guarantee because "the law-abiding citizens of this territory are entitled to have firearms for their own protection, for sportsmanship, for target practice and so forth." Delegate Fukushima had the final word, stating that the guarantee "will protect all the people from [sic] keeping and bearing arms, subject of course to reasonable restrictions." It was then adopted unanimously by the Committee of the Whole. Wilson quotes the report of that Committee stating that the guarantee "will not render invalid the existing laws of the Territory … relating to the registration, possession and carrying of firearms," nor would it "prevent other reasonable restrictions on the right to acquire, keep or bear firearms or other weapons," including prohibitions on "the possession of such modern and excessively lethal weapons as machine guns, silencers, bombs, atomic weapons, etc." Comm. of the Whole Rep. No. 5. All of these referenced laws applied to the people at large, and so it was relevant to say this only because the guarantee protects individual rights. None of these listed laws applied to the National Guard, which was equipped with machine guns and bombs. The state has power to regulate the National Guard unconstrained by the arms guarantee. The Constitution of 1950 was approved by the voters at the general election that year. The Territory became a state in 1959. Revisions to the guarantee were proposed in 1968. Wilson quotes a report from the Legislative Reference Bureau stating: "The historical background of the Second Amendment indicates that the central concern in the right to bear arms was the right of the states to maintain a militia." 1 Hawai'i Constitutional Convention Studies 7 (1968). Yet on the very next page, the report referred to "evidence which indicates that the delegates [in 1950] thought that section [17] was guaranteeing an individual right to keep arms." Wilson further relies on a committee report from 1968 stating: "The right to bear arms refers explicitly to the militia and is subject to lawful regulation." The actual guarantee, of course, explicitly refers to "the right of the people to … bear arms…." Wilson also refers to a document from the 1978 convention claiming that the guarantee "referred only to the collective right to bear arms as a member of the state militia…." But nothing during these later proceedings can change what was actually stated and understood at the 1950 convention. Wilson also claims that the framers in 1950 were aware of United States v. Miller (1939), in which the Supreme Court supposedly held that "the Second Amendment conferred a collective right to bear arms in service to the militia." Miller said no such thing, instead holding only that it could not take judicial notice of whether a short-barreled shotgun was ordinary military ordnance. The Court was not concerned with whether defendant Miller was a member of an organized militia, assuming that the Amendment protects all Americans. Relatedly, Wilson also endorsed Justice Stevens' dissent in Heller that the prefatory phrase "identifies the preservation of the militia as the Amendment's purpose." But as the Heller majority held, the Amendment's operative clause protects individual rights. The Committee on Judiciary of the Hawai'i Senate, in a 1992 report, explained why that logic could not apply to § 17: Article I, Section 17 created a qualified "individual" right to bear arms. A "collective right" theory is logically inapplicable in the context of a state constitution. . . . It is not a right of the counties to maintain militia free of state infringement. Nor could it logically be to allow the state militia to operate free of state infringement. Finally, it could not be a state limitation on federal infringements. By simple process of elimination it must create an individual right to bear arms. Standing Committee Report No. 1788, Feb. 14, 1992, at 5. Besides citing a line from an episode of the HBO series The Wire as authority against Bruen's historical-tradition test, the Wilson court relied on a 1990 issue of Parade Magazine in which Chief Justice Warren Burger supposedly said that the individual-rights interpretation is "one of the greatest pieces of fraud … on the American public by special interest groups that I've ever seen in my lifetime." That quote is not to be found in Parade, but Burger did write there that no one questions "that the Constitution protects the right of hunters to own and keep sporting guns for hunting game any more than anyone would challenge the right to own and keep fishing rods …." Great scholarship. Wilson ends with a digression on history and tradition in Hawai'i. It favorably recalled the 1852 Constitution of King Kamehameha III, which "contained no right to keep and bear arms." That is not surprising, in that the Constitution provided for absolute rule: "The King is sovereign of all the chiefs and of all of the people; the kingdom is his." That recalls the infamous dictum of Louis XIV: "L'état, c'est moi." Under a weapon law of the same year, Wilson relates, "the only people allowed to carry arms were Kingdom officials and military officers…." The monarchy was overthrown in 1893 and the Provisional Government set up, which established the Republic of Hawai'i. Wilson relates that, in 1896, the Republic passed a law prohibiting the carrying of a firearm without a license, but does not mention that anyone could obtain a license on the payment of an annual fee of one dollar, without any other qualification. See Republic of Hawaii v. Clark (Haw. 1897). Hawaii was a U.S. Territory from 1898 until 1959. Its carry restrictions only applied to concealed handguns, which required a permit that would be issued if the person had "good reason to fear an injury" or "other proper reason." We have no idea how strictly such laws were administered. It was not until 1961 that a permit was also required to carry openly. For the above history, Wilson relies on the Ninth Circuit's 2021 decision in Young v. Hawai'i, which upheld the state's ban on open carry and which was vacated and remanded by the Supreme Court in light of Bruen. I have written about Young's faux histoire here. The post-monarchial history reflects the context in which the guarantee of the right to bear arms in the Constitution of 1950 would have been understood. As in many American states, open carry was lawful and concealed carry required a permit. It was not as if, as Wilson depicts, no right of the people to bear arms was recognized. One last point about the historical context in which the 1950 Constitution was adopted. That was only five years after the end of World War II, which for the U.S. began with the attack on Pearl Harbor. When the Hawai'i National Guard was federalized, the Territorial Guard and supportive armed civilian groups stepped up to protect against sabotage and defend against potential invaders. Many of the delegates at the 1950 convention, like our Founders, doubtlessly considered the militia to consist of the people at large who would take up arms in an emergency. Wilson ends with an explanation of how "the spirit of Aloha clashes with a federally-mandated lifestyle" of recognizing the right of citizens to carry firearms. While that was another jab at the U.S. Supreme Court, Wilson found that the defendant lacked standing to raise a Second Amendment defense because he had not applied for a carry permit, a requirement that Bruen recognizes. The Wilson court could have followed the same logic and found that he lacked standing to challenge § 17 as well, in which case no need would have existed to repeal that guarantee of the state Bill of Rights by judicial fiat.

The post Second Amendment Roundup: The Hawai'i Supreme Court Overrules Bruen appeared first on Reason.com.

|

|

|

By Eugene Volokh

From Weaver v. Millsaps, decided Wednesday by the Georgia Court of Appeals, in an opinion by Judge C. Andrew Fuller, joined by Judges Anne Elizabeth Barnes and Benjamin Land:

After Michael Weaver and others acting at his behest posted negative Google reviews of Valerie Millsaps's frame shop business, she published a response, calling Weaver a Neo-Nazi and known felon who was targeting her business and had "threatened to kill other shop members." … Millsaps and her husband own a framing shop in Cartersville. One day in June 2022 while Millsaps was driving her company van, she saw Weaver standing on the street holding a sign that appeared to be antisemitic. Millsaps "displayed [her] middle finger" at Weaver. Weaver, having seen the business logo on the van, published a post on his personal blog asking his followers to leave negative Google reviews of the business. Within 12 hours, multiple negative reviews appeared on the business's Google review page. Weaver subsequently thanked his supporters who had left the reviews and stated, "I'm just getting warmed up! … Total f__king war!" In response, Millsaps posted her own comment on her business's Google review page: My business is being targeted by a Neo Nazi and a member of the KKK. Please disregard the reviews. None of those profiles have ever entered my shop. I am being harassed and bullied by Michael [Weaver]. A known felon of hate crimes. He has targeted many businesses in our town. I refuse to be intimidated by him and his hate literature that he has left at my shop and my home. He has threatened to kill other shop members and flooded their Google reviews with harassing, untrue reviews. You can decide to try my shop and let my experience speak. Please note all date stamps are in a concentrated period of time. I choose LOVE over HATE. Thank you kindly.

According to Millsaps, the frame shop's Google rating plummeted due to negative reviews left by Weaver and his followers, and the shop's business declined. Weaver sued Millsaps for libel, alleging that she had made knowingly false statements about his criminal record, his affiliation with the KKK, and his "terroristic threats to her customers." Millsaps moved to dismiss the complaint …, arguing among other things that her statements were truthful protected speech made without actual malice.

In support of the motion, Millsaps presented her own affidavit, along with a verified answer and counterclaim, stating that Weaver is a member of the Neo-Nazi National Alliance, which advocates "new societies throughout the White world which are based on Aryan values and are compatible with the Aryan nature[,]" and World Church of the Creator, whose founder calls for "total war against the Jews and the rest of the goddamned mud races of the world[.]" Additionally, Weaver co-founded a Cartersville-based white supremacist group working to make America a "Eurocentric Christian Nation." Millsaps presented evidence that Weaver advertises these affiliations to news reporters and on social media and his personal blog. Millsaps averred that, before her personal encounter with Weaver, she was familiar with him, his white supremacist affiliations, and his distribution of antisemitic literature around Cartersville. She knew that Weaver "had a history of violent behavior," including a prior aggravated assault conviction for pepper-spraying an African American man he encountered on the street. {See generally Weaver v. State (Ga. App. 2013) (affirming trial court's denial of Weaver's motion to withdraw his guilty plea). Millsaps also pointed to news articles showing that, on another occasion, Weaver got into a "loud verbal dispute" with a man who was removing his flyers and followed the man with a taser; and that Weaver was given a criminal trespass warning after a Cartersville business owner complained about him placing flyers on cars in the parking lot.} Millsaps also had heard that Weaver had targeted other Cartersville businesses, including a gym that had kicked him out for posting antisemitic flyers inside. According to Millsaps's verified answer, Weaver and his associates left thousands of negative Google reviews for the gym, vandalized the premises, and made repeated harassing phone calls, including one in which the caller threatened to kill the gym owner, prompting the owner to call the police. Weaver submitted a verified response to Millsaps's filings, conceding that he had engaged in "review bombing" on her business's Google page, but denying that he had personally threatened to kill anyone, that he was a member of the KKK, or that he had been convicted of a hate crime.

The court concluded that Millsaps's post was on a matter of public concern, and thus subject to the special procedural protections offered by Georgia's anti-SLAPP statute: "Weaver concedes on appeal that he is 'a public figure,' and it is undisputed that Millsaps's challenged comments were made in response to a 'war' that Weaver initiated on a public forum." And the court concluded that Weaver had no reasonable probability of prevailing on the merits:

Although Weaver challenged multiple portions of Millsaps's post in the trial court, on appeal he focuses only on her statement that he "threatened to kill other shop members." Weaver asserts that this statement is false because he never threatened to kill anyone, let alone multiple people. In determining whether Millsaps acted with actual malice, however, the question is not whether Weaver actually made the threat, but whether Millsaps knew when she made her post that he had not made—or probably had not made—the threat. Millsaps averred that she made her Google post to protect her business and believed the information in the post was true. As noted, Millsaps knew about Weaver's membership in organizations advocating race wars and his history of violent criminal behavior. Millsaps also had heard that Weaver had threatened to kill a local gym owner after the owner kicked Weaver out of the gym. Although Weaver denies personally making any such threat, he has not denied instigating a campaign of harassment against the gym that included negative reviews, vandalism, and repeated phone calls, and he has not shown that no death threat occurred. Accordingly, there is no evidence that Millsaps knew her statement about the death threat was false or probably false. Weaver also argues that Millsaps acted recklessly because her statement "says 'shopmembers.' Plural. And does not specify who was threatened, but rather … allows the reader to come to different conclusions as to who was threatened, and how many people." But "defamation law overlooks minor inaccuracies and concentrates upon substantial truth." Further, "rhetorical hyperbole … cannot form the basis of a defamation claim." Here, Millsaps's use of the plural may have been factually inaccurate, in that she presented evidence only of one death threat. But this inaccuracy, or hyperbole, does not go to the substance of her comments and does not prove actual malice. Because there was no evidence—much less clear and convincing evidence—that Millsaps knew her statement was false, or acted in reckless disregard of its truth or falsity, the trial court did not err by concluding that Weaver likely would not prevail on his claim. It follows that the court did not err by granting Millsaps's motion to dismiss. {In light of this conclusion, we do not address the trial court's other basis for concluding that Weaver would not prevail—that Millsaps's statements were true.}

Thomas MacIver Clyde and Jeffrey Howard Fisher represent Millsaps.

The post Alleged Neo-Nazi Loses Libel Lawsuit appeared first on Reason.com.

|

|

By David Bernstein

It's kind of horrifying that the loudest voices bemoaning Palestinian civilian suffering in Gaza will harshly criticize everyone and anyone–Israel, the US, the EU, the UN Security Council, American Jews, you name it–except for Hamas (and its allies like Iran), and the one thing they won't do is suggest Hamas surrender, even though that would immediately end the war, and also end Gazans being ruled by an oppressive medieval theocracy that steals aid money to build weapons and villas for its leaders. In short, no matter how much they purport to care for Palestinians, their biggest priority is that Israel not emerge victorious over Hamas. I won't go so far as to claim that they don't care about the Palestinians. I will claim, strongly, that they hate Israel much more. A perfectly good (but hardly the only) example is Karen Attiah, who has a sufficiently influential position as world opinion editor at the Washington Post that someone like her deciding that hey, maybe Hamas should just surrender and release the hostages could help move the needle, given that Hamas is counting on world opinion to stop Israel's offensive and keep it in power. Even if Hamas is beyond world opinion, its patrons and allies in Turkey, Qatar, and even Iran are not. And the folks I'm referring to won't even suggest that they want Hamas to surrender for rhetorical purposes. Like, "Of course my preference would be for Hamas to surrender and release the hostages, but if that can't happen, and it looks like it can't, to end the civilian suffering Israel should cease fire." Nope, they won't even suggest that they would *prefer* Hamas to surrender. How twisted does your mind have to be to think Hamas is the relative good guy here? And that you won't even pretend you think otherwise just to help persuade, because you can't bring yourself to even do that?

The post When Hating Israel is Your Priority appeared first on Reason.com.

|

|

By Josh Blackman

I am pleased to pass along opportunities for summer fellowships. First, the James Wilson Fellowship will meet this summer in the Washington, D.C. area. In partnership with First Liberty's CRCD, JWI Co-Directors, Profs. Hadley Arkes and Gerry Bradley, joined by other distinguished scholars, will offer an in-person seminar over seven days in the Washington, D.C. area, on Natural Law and its bearing on our jurisprudence. The course will focus on discussing the central points of a jurisprudence of Natural Law, such as the classic connection between the "logic of morals" and the "logic of law," the properties of moral truths and the principles of judgment, and how we would see certain landmark cases differently if they were viewed through the lens of Natural Law. Our main objective is to restore a moral coherence to our jurisprudence. Fellowship topics fall into two categories: the first half of the week focusing on the foundational principles of Natural Law jurisprudential reasoning, and the second half centering on the practical applications of that reasoning to issues arising in our constitutional order. Second, The Fund for American Studies Summer Law Fellowship, also in Washington, D.C.

The TFAS Summer Law Fellowship in Washington, D.C., is an intensive nine-week program that aims to prepare law students to defend the values and ideals of a free society rooted in individual liberty, limited government, free enterprise and constitutional originalism. Through this immersive academic and professional experience, participants will engage in legal internships, academic coursework, networking events and career development sessions, as well as a law and public policy lecture series with leading constitutional scholars, judges and practicing attorneys. Those selected to participate in the Fellowship program will receive a full scholarship covering tuition, housing and program fees. Awards are highly selective – only 25 students are selected to participate each year.

Apply today!

The post Apply for the James Wilson Fellowship and the TFAS Summer Law Fellowship appeared first on Reason.com.

|

|

By David Post

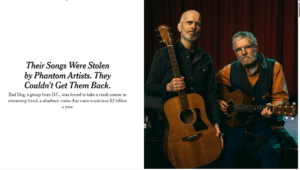

Some of you may have seen the article by David Segal in the Sunday NY Times several weeks ago [available here] about a rather sordid copyright fracas in which I have been embroiled over the past few months. [That's me, seated on the right in the photo]. It's a pretty wild story. If you don't feel like reading the whole NYT article, here's a brief summary of how it unfolded:

Off and on, for 30 years or so, I've been in a duo ("Bad Dog") with a friend, Craig Blackwell, here in Washington DC: Two acoustic guitars, two vocals, original songs. We take the music we make very seriously, but we are not professional musicians; we both had and have careers outside of music. We weren't and aren't in it for the money, but just for the pleasure of making music and the satisfaction one gets from creating something worthwhile and interesting and, perhaps, even beautiful. In early 2023, we recorded an album containing nine new songs ("The Jukebox of Regret"—you can listen to it here) at a local recording studio (Mixcave Studios). After the recordings were mixed and mastered, we posted them (as we had posted other recordings that we had made over the years) on the "Bad Dog" page at Soundcloud.com, a music-sharing website. Several weeks later, a friend told us that she had input a recording of one of our songs (entitled "Preston") into the Shazam app, and that Shazam identified the song right away—as something called "Drunk the Wine" by someone called Vinay Jonge. It pointed her to the YouTube page where the recording was available to be streamed. Well! The YouTube recording was, it was clear upon listening to it, an exact duplicate of the recording we had posted on SoundCloud. A quick Google search on "Vinay Jonge—Drunk the Wine" turned up his recording—i.e., our recording of "Preston"—at all the other major music streaming services (Spotify, Amazon Music, Apple Music, allmusic.com, etc.). [Curiously, Mr. Jonge didn't seem to have any other songs posted anywhere on the Internet. A one-hit wonder!]. We began the process of sending "takedown notices" to each of the streaming platforms, informing them that they, and Mr. Jonge, were infringing our copyright. And then we learned that it wasn't only "Vinay Jonge," and it wasn't only one song; all of the songs on the album had been pirated and were posted on all of the big streaming platforms. Each one had a new song title and a new artist name: - our "The Misfit" had become "Outlier" by Arend Grootveld;

- our "Verona" had become "I Told You" by Ferdinand Eising;

- our "A Drink Before I Go" had become "Drink When I'm Gone" by Amier Erkens;

- our "Pop Song" had become "With Me Tonight" by Kyro Schellen;

- etc.

You might ask: How did we figure this out? Good question! Searching for "Bad Dog—Preston" or "Verona" or "The Misfit" at Google or YouTube or Spotify or Apple Music etc. wouldn't have turned anything up, because the song names had all been changed, and each song was associated with a different "artist." Without knowing how our songs had been re-titled, or the names of those who were taking credit for our work, the infringements were completely invisible to us, out there in the great Internet ocean. So how did we track them down? The answer is: We found these other infringing files after we sent the nine song files to Disc Makers, a commercial CD printing operation, to have them print up some CDs for us to hand out at our upcoming album release show. Disc Makers apparently uses some sort of file-matching software/system to check at least some of the streaming platforms for duplicate files; they found the infringing files, and they sent us a polite note with a list of everything they had found, and informing us that they had put our CD project on "Hold," because the files we sent them "contain previously copyrighted material." Disc Makers, in other words, thought—not unreasonably, I suppose, given the evidence it had—that we were the infringers! Until we were able to persuade them that it was the other way around (which we were able to do by demonstrating that the upload date of the files we sent to SoundCloud pre-dated the upload dates for the infringing files) they wouldn't make the CDs for us. One final plot twist. Now that we had the "artist" names and the new song titles, we could locate infringing files at the streaming platforms, and we started sending out more takedown notices. In response to one that we sent to Apple Music, we got a note back saying, in effect: "The songs you have identified were provided to us by a music distributor. If you have a copyright claim, please direct it to the distributor." And they identified the distributor: Warner Music Group. Well! That was a surprise! Warner, of course, is one of the world's largest distributor of digital music, with thousands of musicians under contract, and a pipeline that extends to all of the big streaming platforms. Apparently, Warner had some sort of relationship with Vinay Jonge, Amier Erkens, Arend Grootveld, and the rest of them under which Warner distributed "their" music to the streaming platforms (and, I assume, took a small percentage of whatever streaming income those tracks generated). Also apparent: whatever system Warner uses to insure that the artists they represent own the copyrights in the material that they deliver to Warner did not function adequately in this case. [The folks at Warner declined my request to comment on this article]

What to make of all this? I am not oblivious to the irony of being confronted with this problem after having spent 30 years or so, as a lawyer and law professor, reflecting on and writing about the many mysteries of copyright policy and copyright law in the Internet Age. Here are a few things that strike me as interesting (and possibly important) in this episode. 1. What's the big deal? The nature of the legally-cognizable injury that we suffered as a result of all this is worth a more detailed look. The unauthorized reproduction and distribution of our songs is, without question, actionable copyright infringement. Blackwell and I, as copyright owners*, have the exclusive right to reproduce, and to publicly distribute, the songs to which our copyright attaches, and to authorize others to do so. We did not authorize Jonge (or his colleagues) to do that. Copyright infringement is a strict liability offense; whether or not Messers. Jonge et al. knew that the files we posted on SoundCloud contained copyright-protected works is entirely irrelevant. It's a slam dunk case. *There are, as the copyright nerds among you well know, two separate copyrights attached to each song, both of which were infringed here: A "musical works" copyright, which protects against unauthorized reproduction and distribution of the song itself (words and music), and a "sound recording" copyright, which protects against unauthorized reproduction and distribution of our particular recorded performance of each song.

But the harm that we suffered as a consequence of those actions is relatively—perhaps vanishingly—small. Remember, we had placed the recordings on SoundCloud for the sole purpose of getting people to listen to them. Thanks to the efforts of Vinay Jonge and his pals, many of our songs have now been streamed tens of thousands of times on Spotify and YouTube. Hooray! There is another injury, of course, and it is the one that really matters, for the two of us, given our particular circumstances. It's not the one arising from the unauthorized reproduction and distribution per se, but the injury arising from the false attribution accompanying those unauthorized reproductions and distributions. That's what really (to use the technical legal term) "pisses us off." That those tens of thousands of listeners now associate "Preston"—a song that Blackwell wrote, and that we have been playing and working on for 30 years—not with Bad Dog, but instead with that elusive genius, "Vinay Jonge." For us, that is largely a "dignitary" harm, an injury to our "person-hood," akin to the harms underlying the torts of libel, or invasion of privacy, or intentional infliction of emotional distress, entirely independent of whether or not we have suffered any economic loss. It's not, in other words, about the money—but no less real for all that. I realize, of course, that for many musicians whose music has been similarly ripped off (see [2] below), this kind of false attribution does impose substantial economic harm. Free distribution of one's work over the Internet has become, for anyone trying to earn a living as a performing musician, or as a composer/songwriter, an indispensable part of getting people to pay you to stream your music, to come to see your live shows, to record the songs you have written, to hire you to teach them how to play the piano or violin or guitar, etc. For these folks, substantial economic harm, in addition to the dignitary harm, can arise from the false attribution.

Interestingly (at least to this ex-copyright lawyer) that injury—the one arising from the false attribution—is not one that U.S. copyright law protects against. Copyright law gives creators a set of exclusive rights which does not include the right to have their works correctly attributed to them. Vinay Jonge's act of putting his name to our song, standing alone, doesn't infringe our copyright. I think this comes as a surprise to most people. It means that if we had authorized Mr. Jonge to distribute our songs to the streaming platforms, and he did so under his own name, while we might well have a claim against him for breach of contract, or for unfair competition, or for "passing off," we wouldn't have a copyright claim against him, because the Copyright Act does not include the right of attribution in the bundle of rights granted to the copyright owner. The copyright laws of many countries—most notably, throughout the EU—do protect the attribution right, and there has been a long-standing debate as to whether, and to what extent, the U.S. should follow suit. I've never been a big fan of efforts to do so, and I don't think I've become one now; the last thing the Copyright Act needs is an additional set of rights to over-complicate an already over-complicated statute. But the whole episode has certainly given me more of an appreciation for the significance of the attribution principle. 2. Scale and automation Though I might like to flatter myself with the notion that Messrs. Jonge, Grootveld, Schellen, and the others chose our music to steal because they loved the interplay between our guitars, or because they were moved by the lyrics to our songs, I'm pretty sure that's not how this went down. While I don't know exactly how our songs ended up on Apple Music and the other streaming sites, here's what I think happened. First off, the names of the infringers—"Vinay Jonge,""Arend Grootveld," and the rest of them**—do not identify real people. The names are all made up; I wouldn't be at all surprised if there were a single person or entity behind all of them.

**Here's the entire list of "artists" whose names appeared with our recordings on one or another of the streaming platforms: Vinay Jonge, Arend Grootveld, Gaston Mailly, Ferdinand Eising, Seth Klompmaker, Kyro Schellen, Amier Erkens, Janco Rossem, Enzo Pruijmboom, Rivaldo Laak, Tuur Jonk, Rashied Amelsvoort, Lennert Olivier, Tjark Warnaar. Fabulous, don't you think? Tjark Warnaar?! The list reads like the roster of the Olympic hockey team from some unrecognizable but vaguely Scandinavian land. And by strange coincidence, each one stole one, but only one, of our songs

And I doubt that anything as inefficient and time-consuming as actually listening to our music took place before the recordings made their way to the streaming platforms. This is a money-making scheme that can yield some serious money, but only if it can be automated to operate at scale. There's a vast ocean of music—tens of thousands of hours of music uploaded every day—that is freely distributed on Instagram, SoundCloud, YouTube, Bandcamp, Facebook, etc. I strongly suspect that "Mr. Jonge"—or whoever stands behind that pseudonym—chooses his targets based not upon musical quality but upon simple availability; he sends out his automated crawlers to prowl the ocean and bring back whatever it finds. An automated name-generator creates a fake artist name, an automated lyrics-analyzer finds a new song name,** and off he goes. **Another of the amusing features of this adventure is that the new names given to the songs were clearly not chosen at random, but always had some semantic relationship to either the original title or to the song lyrics themselves. "The Misfit" became "Outlier"; "Preston" (with the lyric "Preston stuttered and he drank the wine") became "Drunk the Wine," etc.

If he can get a distributor to post your recordings to Spotify and the other big for-pay platforms, you might earn around $0.002 per stream; 10,000 streams will get you about 20 bucks. Not too exciting—unless he can do this for 1,000, or for 10,000 songs, at which point we're talking about real money. Whoever found a way to take our recordings and to re-package and monetize them would be capable, I would think, of replicating that for thousands or hundreds or thousands of songs which are made freely available out there on the Internet. Given the substantial amounts of money you could make that way, I wouldn't be at all surprised if enterprising entrepreneurs, with rather dubious moral codes, are hard at work on the problem. If I'm right about that, then there are thousands and thousands of musicians out there whose music is being monetized by others in precisely this fashion, and who have absolutely no idea this is happening. If you posted recordings on Bandcamp or SoundCloud that were subsequently "Vinay-Jonged," and made available under some fake name at Spotify or Apple Music, you can't find them using the search tools Spotify and Apple make available to you. The only way to find them is for Spotify and Apple to run some file-matching algorithm that compares, bit for bit, the file you uploaded against the files in the Spotify or Apple databases, and that's not something Spotify or Apple will do for ordinary users. I'm no class-action lawyer, and have no intention of becoming one, but if I were I might take some time to investigate this a little further, no? Notice and takedown As described above, we spent a considerable amount of time searching for infringements on the major streaming platforms (once we knew what we were searching for), and then, once we found them, sending in "takedown notices" to the platforms. The Copyright Act's "notice-and-takedown" provision (codified in Section 512(c) and 512(g)) was one of the centerpieces of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act, enacted in 1998. It is one of the least artfully drafted statutory provisions in the entire US Code, but basically it works as follows: The N-and-T scheme gives "service providers"** an immunity from copyright infringement liability, provided certain conditions are met. Such an immunity is immensely valuable, even for relatively small Internet operations, let alone for the Internet giants (YouTube, Spotify, Instagram, et al.) that post tens of millions of user-uploaded files every day, both because (as noted above) copyright infringement is a strict liability offense, and because copyright owners can obtain fixed statutory damages*** of at least $750 for each infringement regardless of whatever actual financial damage they may have suffered.

**"Service provider" is broadly defined to include Internet intermediaries of all kinds: all entities "transmitting digital online communications … between or among points specified by a user, of material of the user's choosing, without modification to the content of the material as sent or received." Facebook, YouTube, Spotify, Instagram, X, TikTok, Reddit … virtually the entire universe of social media platforms, and much besides, are within the definition. ***Section 504(c) provides that "the copyright owner may elect, at any time before final judgment is rendered, to recover, instead of actual damages and profits, an award of statutory damages for all infringements involved in the action, with respect to any one work … in a sum of not less than $750 or more than $30,000 as the court considers just."

The immunity, however, is only available to service providers who, upon receiving a notice from a copyright owner asserting that material residing on the provider's system is infringing, "respond expeditiously to remove or disable access to the material that is claimed to be infringing."** **The provider must also simultaneously notify the user who uploaded the material in question that an infringement claim has been filed, and must allow the user an opportunity to file a counter-notification disputing the infringement; upon receipt of such a counter-notification, the provider must "replace the removed material and cease disabling access to it" within 14 days in order to remain eligible for the immunity.

The N-and-T scheme was quite innovative at the time it was enacted, and extremely controversial as well. Many copyright owners objected to the fact that it placed the burden on them to find infringing material, and that it imposed no duty on the service providers to search for or locate such material. I thought at the time, as a participant in many of the discussions and debates that led up to enactment of the N-and-T provisions, that that was the right call, and I still do. But notice-and-takedown can only perform its task of deterring infringement if copyright holders can reasonably be expected to locate infringing material. That doesn't appear to be the case here. The platforms have the technology available to check their databases for identical copies of copyrighted material, and they use that technology at the behest of some copyright owners whose material is distributed to the platforms by their "trusted partners." Warner Music, that is, can and does get YouTube and Spotify and Apple Music to check for uploads on their streaming systems that infringe the copyright of Warner-represented artists whose music Warner has distributed to the platforms. But those tools are not made available to ordinary users who do not have a contractual relationship with YouTube and Spotify and Apple Music. If I am correct in my speculations about the size and scale of these scam operations, that would appear to be a rather significant lacuna in the statutory coverage. The DMCA itself may point to a way out of this dilemma. Section 512(j) already provides for an additional condition of eligibility for the immunity: A service provider cannot assert the immunity unless it "accommodates and does not interfere with standard technical measures," which are defined as "technical measures that are used by copyright owners to identify or protect copyrighted works that (A) have been developed pursuant to a broad consensus of copyright owners and service providers in an open, fair, voluntary, multi‑industry standards process; (B) are available to any person on reasonable and nondiscriminatory terms; and (C) do not impose substantial costs on service providers or substantial burdens on their systems or networks." I don't, to be perfectly candid, know nearly enough about file-matching technologies whether they meet, or could be configured so as to meet, these requirements. But I think that the spirit, if not necessarily the letter, of this provision can serve as the foundation for some kind of an obligation on the platforms' part to facilitate user identification of infringing material.

The post On Copyright, Creativity, and Compensation appeared first on Reason.com.

|

|

By Eugene Volokh

From Magistrate Judge Robert Norway's report and recommendation in Frank v. Fine (M.D. Fla. Jan. 5), adopted by Judge Paul Byron on Jan. 19:

Plaintiff [Colby Alexander Frank] {a self-proclaimed "white civil rights advocate" and member of the "Goyim Defense League"} here alleges that Defendant [Randy Fine, a Florida legislator] defamed him by publishing certain statements on a social media platform. Those statements include: - "I just got jumped by a Nazi with a camera walking into a widely publicized speaking event just now. I'm fine; not sure today will go down as one of his better days."

- "Clearly, he couldn't take it one on one, because as I left, four of his friends were hooting and hollering on the street corner. I got pictures, though being the cowards they are, most were masked."

- "Here's a pic of the Nazi who jumped me."

- "Here's the Nazi's background! Already being prosecuted for one violent felony. Such losers. Mom must not have hugged him enough."

- "The Nazis have released a two second clip from my ambush earlier this week, thinking it makes them look good. I don't think I've ever sounded more eloquent."

… [These statements cannot form the basis for a libel lawsuit] because they are opinions. Statements indicating a political opponent is a Nazi or coward are "odious and repugnant" and far too common in today's political discourse. But they are not actionable defamation "because of the tremendous imprecision of the meaning and usage of such terms in the realm of political debate." In other words, being called a Nazi or coward are not verifiable statements of fact that would support a defamation claim….

Plaintiff alleges Defendant's statements constitute threats [and are therefore actionable as intentional infliction of emotional distress] and that Defendant "has a long history of conspiring with other political agents … against protected free speech activities as well as abusing his position as a legislative representative." Plaintiff states that he "now has genuine fear for his safety" because Defendant has called Plaintiff's protected speech, among other things, "hate litter." … Florida courts are "reluctant to find claims for intentional infliction of emotional distress based solely on allegations of verbal abuse." Indeed, Florida courts have found no liability when a defendant called a member of the clergy "Satan," and claimed that the clergyman had purchased a luxury vehicle using stolen funds. Other Florida courts have found no liability where the speaker made "vicious verbal attacks" that included the use of humiliating language and racial epithets. Another Florida court found no liability when the deputy director of a port wrote an "ode" about a candidate for port commissioner, including the references "hooker" and "bimbo." The statements alleged in Amended Complaint are no more outrageous than the statements from these prior cases. That a self-proclaimed "white civil rights advocate" and member of the "Goyim Defense League" was called a Nazi is no more offensive than referring to a clergyman as Satan in front of his flock, subjecting someone to vicious and humiliating racial epithets, or calling a candidate for public office a bimbo or hooker. Like those statements, the ones here are not so outrageous that they support a claim for intentional infliction of emotional distress in Florida. To be sure, Defendant's social media statements are unflattering, untoward, and base. Some may even say that such statements are beneath the dignity of someone who holds a political office. But insults, indignities, unflattering opinions, and similar rough language do not sustain a claim for intentional infliction of emotional distress in Florida….

The court dismissed the case on its own initiative; plaintiff hadn't served defendant, nor paid the required filing fee, so defendant hadn't yet appeared. For cases applying a similar rule as to allegations of racism, Communism, and the like, see here. The general rule is indeed that simply calling someone a "Nazi" is just seen as an expression of opinion (the person is evil, or morally tantamount to a Nazi), though specific allegations that a person is, say, a member of a Nazi party or committed some crime stemming from his Nazi ideology might indeed be actionable (if false).

The post No Libel or Emotional Distress Discovery for Being Called a "Nazi" appeared first on Reason.com.

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|